About

The Yellow Light hosts articles and a podcast on the built environment. My name is Jonathan J. Chiarella, and I am the principal author.

What changed my mindset the most in my adult life has been learning about the built environment (towns, cities, infrastructure, zoning, roads, streets, transit). It upended how I understood many things that I took for granted. Several facts went against every “reasonable” assumption.

Take for example, the wide, flat, and straight road. Far from being safer, this road poses a greater danger than does a narrow road. On the wider road, you feel safer if you drive fast. If you feel safer, you drive faster. Higher speeds result in more frequent and deadlier crashes. The feeling of safety had the exact opposite of actual safety. And this was just one of the many lessons that changed my understanding of the built environment.

Shocking Case #101: Staying within the Lines

Many places would be safer if we removed . . .

the double yellow line in the middle, and this is especially true for city streets. It does not teach us anything we don’t already know. No one needs a stripe to tell her to not drive into oncoming cars.

Most people don’t oppose these lines or try to cover them up. This is because we assume that the line better than nothing. The truth, however, is that it is worse than nothing.

The double yellow line encourages you to drive so that your car stays in its lane. A car that obeys these colored lines at all times, however, will not give breathing space to anyone who is walking on the side of the roadway.

On a flat surface with no oncoming traffic, most people who are driving will still get very close as they pass anyone who is walking. The person behind the wheel will resist moving past the double yellow line.

This is the case even when crossing that line would be safer, even when doing so gives more space to anyone in the shoulder, and even when no one is approaching from the opposite direction. The person in a car will assume that all other vehicles and objects will also stay perfectly within their own lanes.

If you drive through areas with large numbers of Amish or Mennonite people, you may come upon a horse-drawn carriage on the road.1 Usually, you wait until no one is driving in the oncoming direction, and then you pass the carriage. In order to pass safely, you have to go over the double yellow line.

Because you saw that there’s no oncoming traffic, you may as well go over the line by another six feet (2 m). This way, you can leave a healthy gap between your car and the horses as you pass them.

The horse-drawn carriage clearly extends past the shoulder of the road and into “your” lane. You wouldn’t think of the painted lines as walls. It is clear that you have to go over the double yellow line when you drive by. When a person is walking inside the shoulder, however, the person who is driving will just drive by without a second thought.

This is how “accidents” happen. And when the pedestrian dies without any witnesses, the driver can just tell the police that the victim “darted” into the road or came from “out of nowhere.” As long as you’re not drunk, the police officer who eventually arrives will write down your account of the incident, then probably probably wish you a good day and let you leave.

As a result, it is safer for people on bikes in the countryside to ride side by side and “take the lane.” If you are on a bike and squeeze yourself into the shoulder, then you are inviting anyone in a car to drive very close to you.

When you bike in the lane, riding two abreast is actually more helpful to someone who is driving than if the people on bikes were riding in a single file. It is quicker to drive past two people who are side by side.

If you just wished that everyone on a bike would ride in a single-file line so that you could drive by at full speed, then stop to consider how dangerous it is to drive within inches of someone’s handlebars. Your paint could get scratched!

- These groups reject personal consumption or ownership of many pieces of technology. As a result, they travel between farms or even from farm to town on horse-drawn carriages. The Mennonites who build your garage or run farmers’ markets, however, will use cell phones for work. They are selective with technology; they do have good business sense.↩

Once You See It, You Can’t Not See It

That staple of North America will never . . .

look the same. I don’t mean fast food or cheeseburgers. I refer to the drive-through.

If I saw a bank with one, it had seemed to be as normal as a bird with wings. After living abroad, however, I can’t see it that way anymore.

The car-only line for the ATM is not a fact of nature, nor is the way we build our fast food joints. We chose to make all that space around these buildings into blacktop. To anyone who walks to the bank or the eatery and has disabilities, we send a message. We say that we will gladly make their lives much more difficult in order to get some extra convenience for people who never want to leave their cars. And almost all of them can walk.

In addition to the unfairness, the drive-through is ugly. No tourist buys a postcard that features scenic parking lots, speedy liquor stores, and slip lanes.

This setup also worsens life for the innocent bystanders. Anyone who walks past the entrance or exit to a business with a drive-through must watch out for cars coming in and out from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.—if not twenty-four hours a day as could be the case with a McDonald’s or a Taco Bell.

And watch out we must because the police and the government say that “safety is a two-way street.” I have to pull out my headphones and be ready to leap into action at a moment’s notice. This need to be vigilant is even more acute when you have mobility challenges. The metal wheels of your wheelchair could scratch the hood of the car that drives into you!

Long ago, people in North America chose to put a ring of asphalt around buildings. Banks, restaurants, houses, and more all sit further apart. It takes longer to walk, and so fewer people walk. Later generations take this situation for granted. “Very few people walk.” “This is the way we have always built banks.”

No one shares photographs from a vacation to a road dotted with strip malls and drive-throughs. You probably think of this location as a place you have to to go to, not a place you want to be at. Would you rather walk at your own leisure from building to building in the plaza of Siena, Italy, or do the same on the Las Vegas Strip?

Now imagine what it is like to roll a wheelchair through the parking lot of a Wal-Mart in July. Even if no one intended to be malicious when making this environment, but the harmful effects are real.

The Boss Fight

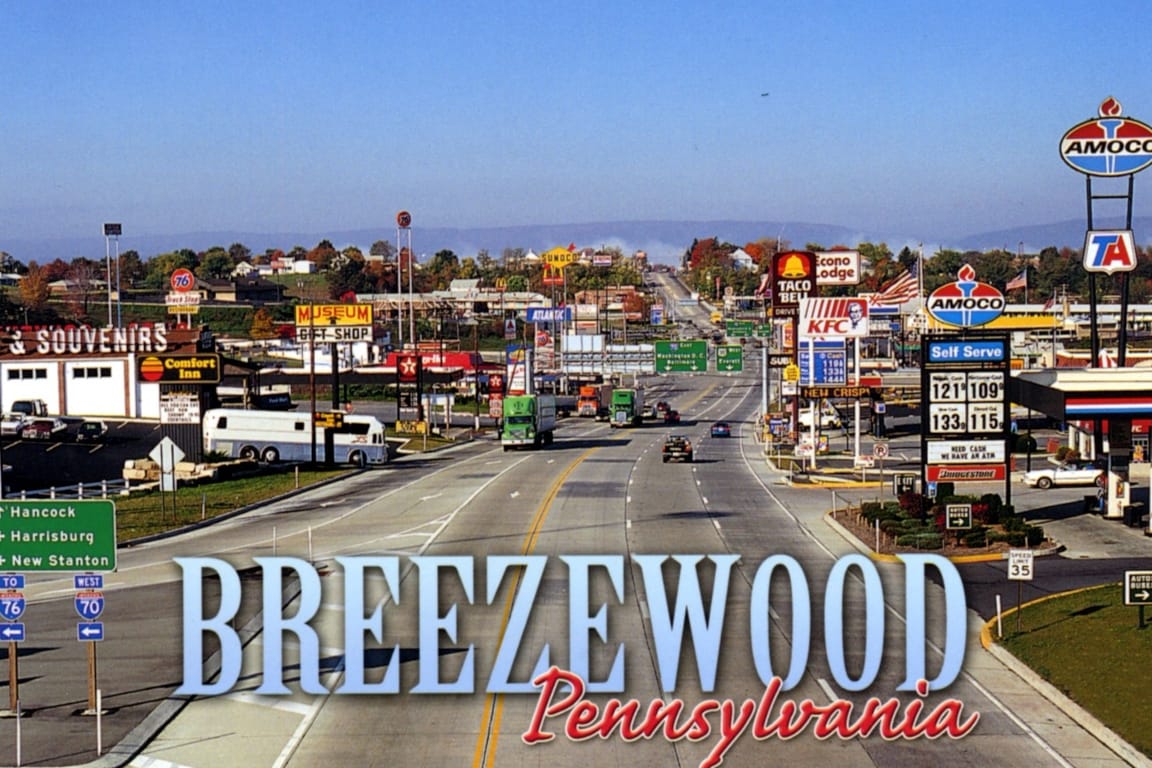

Our supreme pit stop for . . .

a nation on the go—or is it? Even an intelligent and well-educated person such as Jeopardy! champion Ken Jennings considered this conglomeration of chain stores and stroads to be the result of an odd compromise between the policies of the interstate highway system and the state’s turnpikes.

A keen observer will note that the slowdown itself is not the greatest issue, and that neither capitalism nor American culture is the culprit for this monstrosity of development. The problem of stopping in the middle of highway is a problem because it means that the high-conflict zones and chain shops are the only things that can survive. The inconvenience to people who want to drive fast is secondary to that.

Some Americans get frustrated when cars do not hit their natural pace of 70 mph (115 km/h). This is an odd speed to fixate on. We live in a world where, for several decades, trains have been able to reach 200 mph (300 km/h).

I don’t doubt that a minority of people do like to go fast for the sake of going fast. After all, we have professional race-car drivers, spectators, and children who dream of winning Formula One.

This doesn’t describe most people, however, and the focus on speed misses the point. The typical person wants to reach a destination quickly, not move fast for its own sake. If most people simply wanted to go fast, then they would all head over to the nearest amusement park and ride on roller coasters all day.

Taking issue with the focus on changing speeds is like splitting hairs, however. The environment already failed for more significant reasons. It doesn’t deliver efficient throughput or a place that is welcoming to anyone not in a car.

All of this is downstream of an earlier blunder. We went all in on a transportation system where eighteen-wheelers hauled all the goods, people traveled in private automobile, and both would depend on wide highways that criss-crossed the continent.

The network of gas stations, highways, and ample parking did not simply reveal a common preference. The North American landscape is the result of governments at all levels and corporate lobbyists who worked hand in glove with them.

Many writers have unknowingly repeated propaganda by General Motors that Americans have a love affair with the automobile. Some commentators remark that because most people do drive they prefer to drive. It seems to be that they tolerate being stuck in traffic and paying car insurance for the privilege of driving.

This reasoning, however, falls apart when you apply it elsewhere. Would you look at a tilted pool table and say that the eight ball “chooses” to go into the pocket? Would you serve nothing but fruit punch at a party and conclude that because people are drinking your fruit punch that we need to ban anything that isn’t fruit punch?

Scenes like Breezewood’s are rare when we separate use cases. High-speed roads are thoroughfares that connect destinations. Low-speed streets make up those destinations. It’s when we try to mix the two use cases into one place that we get “stroads.”

The Swiss Army Knife has many functions: magnifying glass, scissors, ruler, saw, flat-head screwdriver, Philipps-head screwdriver, and several knives. It is very useful for camping and backpacking, but it’s not ideal for all purposes.

Can you build a house faster with a saw, measuring tape, and a screwdriver or with one multi-tool that does it all? How would you feel if your tax dollars went to the factory that makes multi-tools and if construction sites prohibited rulers? And would you be surprised if all the buildings looked shabby?

You Don’t Know What You Don’t Know

These problems escape . . .

the understanding of people who only know one way of designing towns. It doesn’t matter if that way is good or bad.

Those who enjoy a human-oriented environment take it for granted. People in a car-centric environment think only of driving past most public spaces as quickly as possible.

Someone in Japan may say, “Yes, of course, those shopping zones and izakaya alleys need to be narrow and pedestrianized, and the delivery vehicles need to be motorized scooters, vans, or Kei trucks. And instead of driving here, visitors can just take the subway.”

It sounds simple enough. This person might not be able to imagine how badly anyone could mess this up.

In contrast, an American may say, “It would be nice to have more grassy area by the playground, but if we don’t dedicate a lot of the space to blacktop, then where will I park my car? Maybe I could walk the quarter-mile. My kids definitely could, and they do need the exercise, but it just isn’t safe. Besides, all the other parents drive. Some cyclists and granola types wanted to have a multi-use path here, but if we did that, then we would lose four parking spaces! And besides, not everyone can walk, you know. Expecting people to walk is able-ist.”

More people are unable to drive (too young, too old, low-vision, etc.) than are unable to walk. In any case, people can fully enjoy paved surfaces and nature paths from a wheelchair. People who use motorized wheelchairs cannot just pop their wheelchairs in a car trunk and be on their way. They need an accessible bus to get to the park or they need to ride their wheelchairs along the sidewalk. Our speaker, however, might not be able to imagine a world where a car is not the default option for every trip for every person.

The baseball “park” for the Los Angeles Dodgers lays bare our skewed priorities. Green space is scattered and minimal. No train stations are nearby. You wouldn’t guess that this is hosts the sports team of the second-largest city in the USA.

You would be forgiven if you thought a fire burned everything down. Downtown Houston in the 1970s looked as if it had just emerged from a war.

A Tale of Two Cities

Cue the eye-rolling and the scoffing . . .

from the average person in Canada or the USA at this point. This person could follow up with excuses. “Of course, things are bad here, but our mayor isn’t evil, and our engineers aren’t stupid. All the accidents are from people who just can’t drive well.”

People are correct when they insist that the various people in charge aren’t evil. But that’s a bit like assessing the justice of slavery based on the personality of the enslaver.

Whether your mayor is a good or a bad person doesn’t make a difference either way.

The speaker may add that this town specifically suffers from a plague of “bad drivers.” With this mindset, there is nothing wrong with the design of the roadways. The problem lies squarely with the humans this town got saddled with.

Because people in nicer places can drive better, it is possible for somebody to become perfect. We need to educate, punish, and police more people. Design choices are irrelevant. “What’s next—‘racist roads’? Ha!”1

In reality, people elsewhere do not possess superpowers. The driving skills of the Danish or the Japanese aren’t any better than those of the Canadians. They don’t plow into pharmacies because they don’t have to drive as much. When they do drive, they go more slowly and for shorter distances.

In most of North America, the situation is different. For an aging resident, the only choice is between becoming housebound or driving often, fast, and for long distances until someone is killed.

Another refrain is the following. “Sure, things look nice in Europe, but you can’t compare a young country such as ours with an old country such as the Netherlands—and especially not when bikes are simply part of Dutch culture.”

In the mid- to late-twentieth century, you get a different picture. Back then, “paradise for bike riding” did not describe the Netherlands.

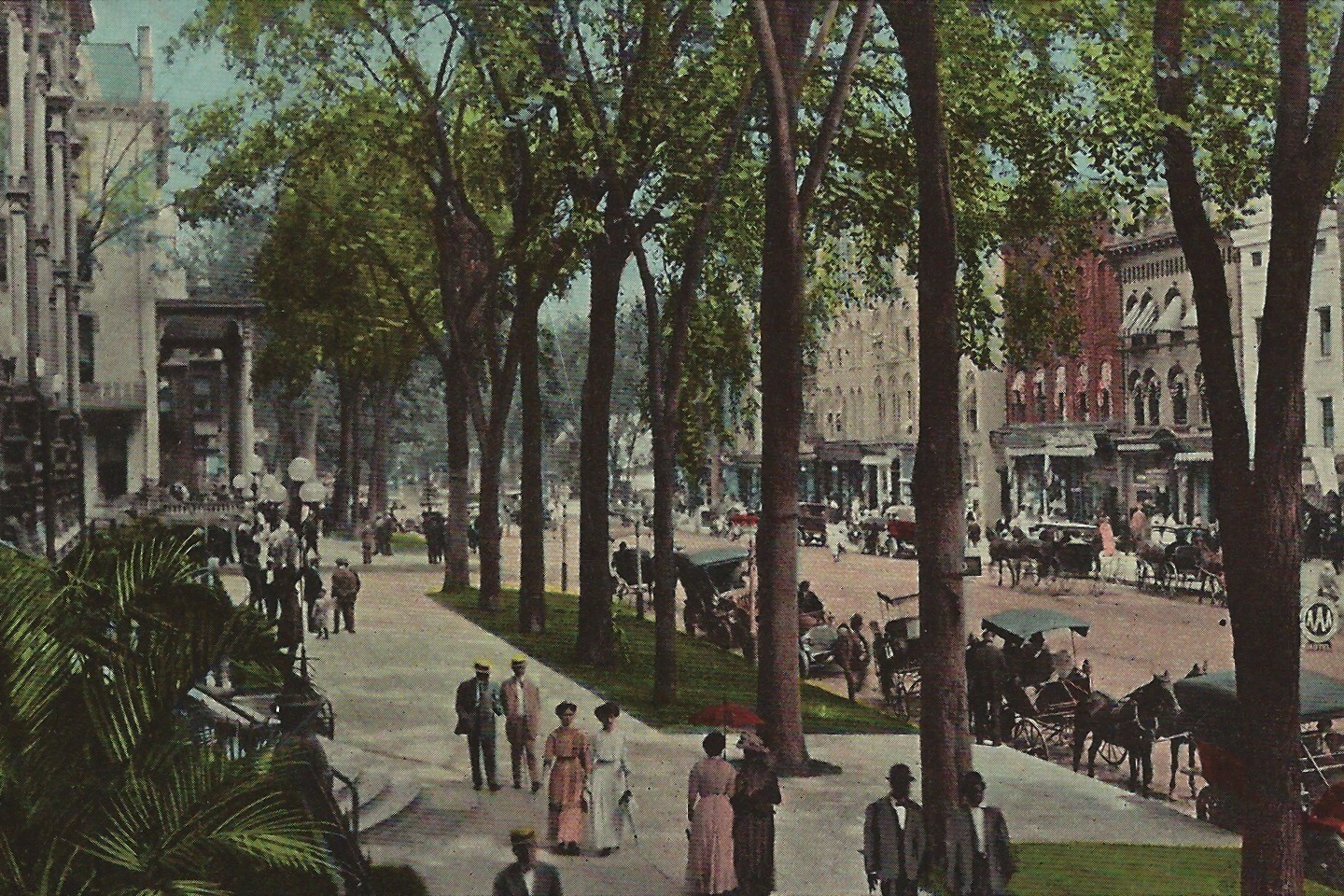

For its part, North America was not destined to revolve around the car. As the saying goes, these cities were not built for the car; they were bulldozed for the car.

You get a very different picture of Cleveland or Kansas City when you see how they looked a century ago. And electrified trolleys (a.k.a. trams or streetcars) ran up and down cities—even the places with only ten thousand thousand residents.

In the 1960s, Amsterdam was a city that was rebuilt at a time when the automobile was king. It was after World War II but before the Stop de Kindermoord movement and major reforms. When almost everyone was forced to drive a personal car, no one was happy—not even those who like to drive.

Today, the photograph of the congestion in Amsterdam seems quaint to anyone who has spent time in Los Angeles since the 1970s.

- Developers, town councilors, mayors, homeowners, bankers, federal agencies, and realtors walled off certain neighborhoods, planted actors, routed interstate highways through African American neighborhoods, and manipulated prices as if they were villains on Scooby-Doo. This sabotaged the living standards and political power of certain groups of citizens. To mock research in this area and dismiss it as studies on “racist roads” is like mocking the idea that the digestion of millions of cattle could have an effect on the methane footprint of meat production.↩

“The Yellow Light”?

A specter haunts the intersection . . .

every day, and we never think about. No one taught it to us. And yet we all know its face.

Most of us see a traffic light every day. It has three colors: green, yellow, and red. Red light: “Stop.” Green light: “Go.” Simple enough, right? Even children can master the game of red light–green light.

And yellow—what does it mean? On paper, it warns anyone driving to slow down. The driver should prepare to stop for the red light that will appear soon. But, in practice, what does the yellow light signify?

Pretend you’re a space alien who can observe humans. From only watching human behavior, would you think that the yellow light says, “Slow down and get ready to stop”? Probably not.

If the traffic light changes from green to yellow, then you know that a red light is coming up soon. No one wants to get stuck at a red light, then sit and wait for several minutes.

As a result, as soon as we see the light change from green to yellow, we feel the urge to act quickly in order to not be trapped. We develop a habit or speeding up when yellow shows up.

The yellow light is the greatest contradiction that most Americans deal with on a daily basis. We know that the transition from the green light to the yellow light officially asks us to slow down. We also know that the yellow light beckons us to go very fast.